The Covid-19 pandemic is hitting the bottom line of banks from every direction.

The economy’s virus-induced slowdown has led to a decline in traditional loan demand, tighter margins as interest rates cave, and a dropoff in bank stock prices. Banks are also facing rising costs, with the pandemic presenting operating challenges at every turn.

The pandemic’s impact on banks showed up to some degree in first-quarter earnings reports. This month’s second-quarter results are giving a broader indication of where the industry is headed.

But much is still to be determined as analysts predict industrywide earnings will drop up to 60% this year compared to pre-Covid-19 estimates.

Banks, recalling the last recession, acted fast to protect their balance sheets in the first half of 2020. They set aside billions of dollars for reserves and doubled down on customer-relief programs.

Those tactics were temporary solutions.

“What they’re going to do or what the effect of the pandemic will be on them will really depend on how the pandemic will unfold itself,” said Yongqiang Chu, a professor at the UNC Charlotte Belk College of Business.

Here are four major ways banks have been hit, how they are reacting and what the long-term implications are:

Loan losses

Credit deterioration is the No. 1 issue facing the banks, said Gerard Cassidy, an analyst at RBC Capital Markets. He said delinquencies and defaults — and the resulting write-offs — will be a problem into next year.

Determining how many loans will move into default is difficult, Cassidy said. The banks sought to delay fallout from the virus, offering borrowers forbearance and deferral agreements. Any default decisions will be pushed into the third and fourth quarters, he said.

Mike Mayo, an analyst at Wells Fargo & Co., said loan losses, commercial and consumer, could increase nearly threefold over the next two years.

Banks started preparing early.

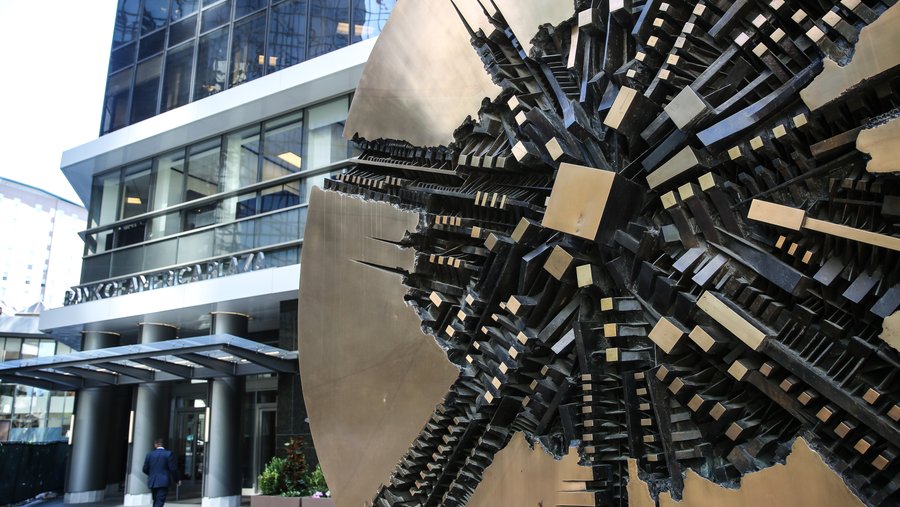

Charlotte’s top three banks — Bank of America Corp., Wells Fargo and Truist Financial Corp. — set aside a collective $7.6 billion for loan-loss provisions in the first quarter alone. Banks put more aside in the second quarter.

Federal officials stepped up to help. Liquidity facilities flooded the markets with cash. National programs, such as the Paycheck Protection Program and the Main Street Lending Program, were created to help stave off immediate commercial-loan defaults. Assisting those businesses brought jobs back, partially stifling defaults on consumer credit cards, mortgage payments and auto loans.

However, the federal programs are not a permanent solution, said Jeff Buchbinder, a market strategist with LPL Financial Research.

“In some cases, we might be delaying bankruptcies rather than eliminating them,” he said.

Buchbinder said bankruptcies will trickle in over the next year or two, although not at the same scale as what happened in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008. He named energy companies as one sector to watch. That could create some problems for banks, considering their sensitivity to the economy and corporate performance.

Banks need to keep lending to boost economic recovery, Buchbinder said, but they also need to make sure those loans are strong and profitable.

Interest margins

The banks are also navigating rock-bottom interest rates.

The Federal Reserve slashed its key benchmark rate to nearly zero in March and has no plans to increase it. The prime rate dropped to 3.25%, down from 5.5% a year ago. Some estimates predict that rate could fall below 3% in 2021, according to Bankrate.com.

Mark Vitner, a senior economist at Wells Fargo, said with no danger of inflation and plenty of liquidity, the low-rate environment could extend in 2022.

Another factor affecting rates is the Fed’s Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility, which allows the regulator to buy individual corporate bonds. Ajay Patel, a finance professor at Wake Forest University’s School of Business, said this program is good for businesses but puts more pressure on bank margins.

“The amount of money they can make on borrowing and lending has diminished quite a lot,” Patel said.

Alternative revenue sources are helping banks offset some of the losses. The PPP, for example, is giving banks of all sizes a needed boost when loan opportunities are scarce. Lower mortgage rates are leading to a boom in refinancing, adding more income to the balance sheets. Market volatility gave the big banks more trading revenue in the first half of 2020 — a trend likely to continue if the virus progresses.

Mayo said the negative impacts on margins are not on the same scale as potential loan losses. He said, for some banks, the second quarter could be the worst one for margins. That’s when rate cuts had the greatest impact.

Chris Marinac, research director at Janney Montgomery Scott, said his concern is the excess cash sitting in low-yield balances. That could be a downside for PPP loans at 1% interest, for example.

But Marinac said it’s more important to have the available cash in a downturn. Bank deposits, in general, are higher than usual thanks to the federal programs and economic impact payments. This may mean more interest payouts in the short term, but he said it’s good for the long term.

For now, banks need to keep low-rate loans as short term as possible, said Randy Adcock, CEO of American Bank of the Carolinas. They also need to fix rates based on what they think is affordable, even once the pandemic subsides and other rates increase, he added.

It’s a balance bankers are used to finding. “Just like we’ve always done — banks, we’ll survive,” Adcock said.

Share prices

Bank stocks took a hit during the pandemic and have yet to recover. The Dow Jones U.S. Banks Stock Index, which includes BofA, Wells Fargo and Truist, was at 502.93 on Feb. 20. By March 23, it had fallen to 263.42. It had rebounded some to 330.90 at market close on Tuesday.

Buchbinder said LPL downgraded the financial sector to neutral a few months ago and remains confident in that decision.

He said bank stocks were already underperforming, and that hasn’t changed since the pandemic. In July, the S&P was down by 2% year-to-date — comparatively, the banks were down by nearly 40%, according to FactSet. LPL prefers the technology, health care and communication services industries, he said.

Mayo said he thinks investors have “recency bias” from the financial recession.

“In other words, if there’s a problem, there’s an implication that banks are the problem, as opposed to this go-around when banks are part of the solution,” he said.

Banks are still returning capital to shareholders. The Fed did halt dividend increases in the third quarter. Most banks are maintaining their dividend rates, although Wells Fargo was forced to cut its rate. Federal regulators also stopped stock buybacks earlier this year.

Future share prices depend on the virus, Buchbinder said. Bank stocks will bounce back if there is an improvement, but a second wave or extended shutdowns would have the opposite effect, he said.

Marinac agreed, noting a Covid-19 vaccine as another turnaround point.

He said the bank stocks are cyclical — they typically dip in recessions and improve as the economy does. Investors also tend to gravitate toward high-growth technology companies. This time is no different.

Expenses

Banks withdrew annual expense targets earlier this year, citing economic uncertainty and rising costs due to Covid-19. Technology investments, safety equipment and work-from-home policies initially added to those expenses.

Marinac said many banks will absorb the hit this year and instead tout savings plans for 2021.

Banks want to show they have more earnings capacity than the market suggests, Marinac said. They also want an optimal outlook in place when they resubmit capital plans to the Fed later this year.

Cassidy said personnel is a big cost burden for banks. He thinks layoffs are imminent. Wells Fargo, for example, is planning to cut thousands of jobs starting this year. Adding to Wells Fargo’s situation, however, is the additional scrutiny from investors and regulators, a byproduct of the bank’s fake-accounts scandal in 2016.

Some banks are trying to hold off on job cuts. BofA CEO Brian Moynihan pledged to avoid layoffs in 2020. BofA is also in a healthy position. Weaker banks do not have this option, Patel said.

Cassidy said branch networks will also see cuts. The pandemic is accelerating a decade-long trend for fewer physical branches, as more customers turn to online and mobile banking.

However, branches will not disappear altogether, Cassidy said. Bank executives say customers still see the value of branches. Others use them to build physical presences and name recognition in new markets.

Total local employment

| Rank | Prior Rank | Business name |

|---|---|---|

1 | 1 | Atrium Health |

2 | 2 | Wells Fargo & Co. |

3 | 3 | Walmart Inc. |